Congratulations! Lots of extra corks should be popping now in the wine region of Champagne, France. They have won the right to party party party! And here’s why…………………

The Champagne Region was selected by Wine Enthusiast Magazine as

the “Wine Region of the Year” for 2018, and

2018 was the best harvest in over a decade.

Isn’t there always good reason to celebrate Champagne? You don’t need food to drink it, and yet it is one of the most versatile wines for food pairing. Champagne will always be compatible with food with just a few exceptions. And don’t forget those famous bubbles. There are supposed to be 10 million of them in a Champagne flute or 50 million in a bottle. They dance on your tongue!!! What is a celebration without Champagne? In my opinion, boring! And true Champagne can only be made here in Champagne, France.

Does Champagne really need an award?

Yes, I think so! Read on to find out why……….. The Wine Enthusiast Magazine has been in print since 1988 to provide information on the world of wine and spirits. They publish hundreds of wine reviews monthly plus coverage of wine and lifestyle topics such as travel, restaurants and notable sommeliers. About 800,000 people read their magazine. They are one of several major wine publications (Wine Spectator, Wine Advocate, etc.) that are available as resources for winelovers and consumers. Nineteen years ago the editors of Wine Enthusiast began their “Wine Star” awards program to honor individuals and companies that make outstanding achievements in the wine and alcoholic beverage world. They have nominees in 16 categories including everything from Person of the Year, to Winery of the Year – American, European and New World, Winemaker of the Year, etc. Yes, I know there are many opinions about the value of wine reviews, awards and points, but I personally am eager to hear someone else’s opinion, especially if they have more knowledge than me. I’ll bet none of the Wine Star winners turn down their awards!

Right now we are most excited about the “Wine Region of the Year” for 2018 award. The Champagne Region of France is this year’s winner and was honored at a black-tie gala at the Nobu Eden Roc Hotel in Miami on Monday, January 28, 2019. Our friend Marcello Palazzi, Regional Manager of the Winebow Group, attended the celebration and was kind enough to share some pictures of the event with us. The winners of all the categories were also announced in the Wine Enthusiast’s special “Best of Year” issue.

Photo courtesy of Marcello Palazzi

What does it take to be a “Wine Star” winner? According to Wine Enthusiast: “Among other attributes, energy, courage, groundbreaking vision and business acumen.” The Champagne region is unique and historic and leads the world in high-quality, bottle-fermented bubbles. They are creative and take stylistic latitude while still meeting all of the many regulations they are legally required to follow, more than any other appellation in the world. Their emphasis is on quality and continuous improvement. They have also grown the Champagne brand while staying true to the legacy of their properties. We obviously think Champagne is a winner since the United States now consumes more Champagne than any other country, including the United Kingdom who was the largest export market for Champagne for many years.

As a 2018 nominee, Champagne was in very good company with Franciacorta, Italy; Galicia, Spain; McLaren Vale, Australia and Sonoma County, California. I would have been delighted to learn more about any of the nominees; however I truly love Champagne (along with every other kind of sparkling!) and am anxious to learn more. Some of you winelovers may remember that last year’s “2017 Wine Region of the Year” winner was Southwest France which then became my passion for numerous months as I researched it, planned and completed a very special wine dinner for some local winelover foodie friends. You can read all about it in previous articles on my forkandcorkdivine.com website.

The best harvest in over a decade?

Should we care about the details of the 2018 harvest and how great it was? Yes, in fact each year’s harvest makes such a difference in many wine regions that forkandcorkdivine.com and our winelover foodie friends devoted an entire article and wine dinner last year to the topic of “vintages”. You can read about it on my website.

The weather in Champagne is full of dangers. Winter frosts can be severe enough to kill the grapevines. Spring frosts can destroy the buds. Cold rainy spells in June can disrupt flowering. Mildew often sets in. Summer often brings violent storms and hail causing severe damage to the vines and clusters. Champagne’s weather is quite a lot like the weather in the US Pacific Northwest. But in 2017 almost 300 million bottles were produced in the Champagne region with an additional 10 million bottles predicted this year. Unfortunately Bordeaux and southern French wine regions had a tougher time as they were blighted by that nasty mildew!

What made this year so different? The winter was unusually wet, setting records. This recharged water tables that the grape vines need to get them through hot dry summers. And the summer was sweltering hot! Because of the heat, vines evolved quickly, and harvest was able to begin in August instead of the usual September. The Comité Champagne establishes the harvesting dates every day for each of the crus. 2018’s harvest began on August 20, the fifth time in fifteen years that the start was so early. Maxime Toubart, president of the Champagne Vintners Union, SGV, called the year “exceptional in quantity and quality” and “didn’t have a single grape go rotten this year”. In years when the harvest is outstanding, producers make vintage wines which require using only grapes from that particular year. These bottles are also 30 to 50% more expensive! The abundant harvest also lets wine-growers and producers rebuild their very low supply of reserve wines which they need in case of poor harvests in the future. If there are no surprises, and the champagne makers develop the wines to their full potential, this could be the vintage of the century!

Here is what some of the best Champagne makers had to say about the 2018 harvest: Eric Lebel, Chef de Caves of Krug, said “We have never seen such a beautiful year for as long as we can remember”. Gilles Descȏtes, Chef de Caves of Bollinger, said “I have never seen anything like that before! All the grapes varieties in all the sub-regions of Champagne were incredible in term of quantity, potential alcohol and sanitary conditions”. Florent Nys, Chef de Caves of Billecart-Salmon, said “The 2018 harvest is remarkable as nature has been particularly generous with us. The ripeness of the grapes was exceptional with very little malic acids and perfect sanitary condition”.

Well aware that a harvest like this one may not happen next year, or the year after, French winemakers are considering how to change their practices to adapt to the weather changes that seem to be more the norm instead of exception. Thirty years ago harvest started as late as October, but now August is becoming more usual. Whether it is all about climate change or not in the future, the quick takeaway here is that we can now expect to look forward to some fabulous Champagne coming on the market in three years!

Preface

I am obviously neither a wine professional nor a professional writer, but I am a winelover foodie who just doesn’t want to stop learning about wine! There is always more to learn: The grapes – there are so many of them!!! Where they grow – there are so many regions I want to know about. The people who grow them – they know the terroir better than anyone. The people who make the wine – they put their whole life into that bottle! And what food should I pair with it to make the experience complete? Whenever I research a wine region or country, I utilize as many sources as I can possibly find because my objective is to provide correct information. I pour through every wine book that I have on hand from Jancis Robinson’s and Hugh Johnson’s “The World Atlas of Wine”, to Karen MacNeil’s “The Wine Bible” and Madeline Puckette’s “Wine Folly:Magnum Edition” and anything else at my disposal. The internet is a major assist as I look through every topic I can think of that seems to be relative even if in some small way. It is amazing what little tidbits of info can be found. What really makes it interesting are the specialty books that seem to come my way just at that very moment as I’m reading about the topic. I was reading an article by Madeline Puckette on her winefolly.com website, and she mentioned a book published in 2017, “Champagne: The Essential Guide to the Wines, Producers, and Terroirs of the Iconic Region”. The book was written by Peter Liem, an award-winning wine writer, wine editor, tasting director for Wine and Spirits magazine and Champagne consultant just to mention part of his credits, and he has lived in the Champagne region for over a decade. The book also comes with a complete detailed set of maps of the region. Peter’s point of view is from the terroir of the region which he says is “as fundamental to champagne as it is to any other wine”. I really enjoyed reading this book and highly recommend it especially if you are an avid winelover, researcher of wine regions and want to get down into the “dirt”.

of the Iconic Region”

Now is the perfect opportunity to take my wine adventure to another region and learn something new, or just brush up on current knowledge about Champagne. We will keep it simple as we delve into where it is made, how it is made, how to serve it, how to pair it plus a few bits of trivia.

A bit of history about the region

The Champagne wine region AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrȏlée)is in northern France in the province that bears its name. You can drive northeast out of Paris about 90 miles to a small range of hills carved in two by the River Marne and be right in the center of Champagne where sparkling winemaking began as early as the 1700s. Limoux may claim to have made the first Brut sparkling wine in the 16th century; however, quality wine was produced here in the Middle Ages and continued when great Champagne houses came to be in the 17th and 18th centuries.

There are currently 320 villages in the Champagne appellation in a total of 17 areas according to the Union de Maisons de Champagne, the UMC. Some maps don’t include the lesser known villages which tends to complicate things a bit. Also numbers tend to differ slightly depending upon which source is used. The towns of Reims and Épernay are the commercial centers of Champagne. Reims is in the north and Épernay is located on the south side of the Marne.

There are 83,000 acres of vineyards here along the 49th parallel producing an average of 850,000 bottles of Champagne a day from some 275,000 separate vineyard plots.

The region, which is near the northern limit for growing grapes, is made up of chalky soil that retains the heat and allows for good water regulation for the vines. There is a large natural cave network below the ground perfect for cellaring the wines.

Champagne was a crossroads for military and trade routes and was devastated and ravaged numerous times. It wasn’t until the 1660s that enough peace prevailed thus allowing advances in sparkling wine production during the reign of Louis XIV. Prior to that time “still” wines, slightly effervescent but not bubbly, were highly prized from this area. In fact the Champagne house of Gosset was founded as a still wine producer in 1584 and is currently in operation. Others with a similar history are Ruinart (founded 1729), Taittinger (1734), Moët et Chandon (1743) and Veuve Cliquot (1772). There was a running feud between the region of Burgundy and Champagne over who produced the best red wine almost to the brink of a civil war, but as Champagne winemakers turned more towards making those bottles of tiny bubbles, the rivalry eventually waned. Champagne production went from 300,000 bottles a year in 1800 to 20 million bottles in 1850 and never looked back! Sales have quadrupled since 1950. Sales for 2017 were over 307 million bottles.

Should we thank Dom Perignon for Champagne? Pierre Perignon was a cleric, who along with some other innovative clerics, provided techniques that helped the evolution of Champagne making. Perignon was the procurer in charge of goods (the cellarmaster) at the Abbey of Hautvillers, just outside of Épernay, which is now owned by Moët & Chandon. He was an avid winemaker and savvy businessman, increasing the size of the abbey’s vineyards and the value of the wine produced. Supposedly he and his fellow clerics were the first to master the art of making clear white wine from red grapes. He was also first to keep grapes from different vineyard lots separate and to practice blending. He also experimented with putting Champagne in glass flasks instead of wooden barrels where it oxidized. He also started to use corks to seal the bottles. He tried unsuccessfully to eliminate the sparkle in the wine as did all of the other winemakers at that time. We can only hope that one day he decided the sparkle was a business success! So it appears that our famous cleric did not invent Champagne, but he certainly helped to perfect it.

Another person we should be thankful for is the Widow Clicquot. She almost single handedly kicked off the industrialization of Champagne in the early 19th century. There is a very interesting book all about her called “The Widow Clicquot: The Story of a Champagne Empire and The Woman Who Ruled It” by Tilar J. Mazzeo.

The grapes of Champagne

There are just three grapes used in Champagne and the two most planted grapes are red: Pinot Noir and Meunier. This is quite unique since most of the wine produced here is white sparkling wine. The clear juice is pressed off the skins before any color can be imparted to the wine. The third grape is Chardonnay. Each of these three grapes has its own distinctive needs and assets thus determining why some are planted in certain areas of the region but not in others. In most cases the grapes will be blended.

Pinot Noir provides structure, weight and power, and now dominates in acreage at about 38% according to the Comité Champagne website.

Meunier (Pinot Meunier) aka “Miller’s Pinot” grapes have a characteristic speckled appearance. This gives a fruitiness to the wines. Many non-vintage Champagnes have a higher percentage of Meunier. It’s easier to grow, is less prone to frost damage and used to dominate the vineyards now with about 32% of total acreage. This grape is grown only in Champagne.

Chardonnay grapes (the remaining 30%) are usually planted in the chalkier sites and produce a more austere and elegant styles of wine. The wines with longer life are usually based upon Chardonnay.

There are also some heirloom grapes in the region, but they are cultivated in very tiny quantities. These are: Arbanne, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris (Fromenteau) and Petit Meslier which according to the Comité make up about .3% of the vineyard plantings. These grapes are not easy to grow, and forgotten about when replanting after the phylloxerra outbreak in the late nineteenth century. There are a few growers making blended Champagne from these grapes today, one of which we will highlight later.

The five main vineyard areas

Since 1927 Champagne has been legally divided into 5 main wine producing areas: Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne, Cȏte des Blancs, Cȏte de Sézanne and the Aube or Cȏte des Bars. These five areas are usually not listed on the bottle. They cover 84,000 acres of planted vineyards which are further divided into 17 sub-regions collectively producing as many as 320 million bottles per year. Each sub-region has a slightly different style or focus. Almost three-quarters of the vineyards are in the Marne Département of France, and all of them together would fit into the city limits of Denver, Colorado.

The 320 villages are classified as Grand Cru (17), Premier Cru (42) or just Cru. All the vineyards of an entire village in Champagne are classified which is different than the Burgundy system of classifying a single vineyard as Premier or Grand Cru. The most highly regarded Grand Cru villages are located in the Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne and Cote des Blancs. Each cru or village has their own specific characteristics. There are over 15,000 growers overall who own 90% of the vineyards. Fortunately we winelovers don’t really need to be concerned about the name of the village – unless we want to be – because in most cases the Champagne is identified by the name of the maker, not the village. Most of the grapes are sold by the grower to the Champagne Maisons (houses) or makers.

Montagne de Reims

(The mountain of Reims), grows 40% Pinot Noir, 36% Pinot Meunier and 24% Chardonnay. Many tȇte de cuvée wines come from the major Champagne wine firms called “houses” of this region. Located in the most northern part of the area between the Marne and Vesle Rivers, the region stretches east-west for 30 km and north-south for 6-10 km. It is argued that this is the most famous of the sub-regions due to three factors: (1) Reims is located here and is oft considered the heart of Champagne, (2) There are nine Grand Cru villages here, more than any other region and (3) It produces amazing wines! The average annual yield ranges from 15-35 hl/hectare from an area of some 2000 hectares. There are 97 villages in the region: Grande Montagne Reims (25), Massif de St. Thierry (17), Monts de Berru (5) and Reims: Vesle & Ardre (51). Montagne de Reims is definitely Pinot country! The wines of this region have body and strength in the blend due to the Pinot Noir, and are mostly on the south facing slope.

Comité Champagne

In Reims you will find the famous cellars of Louis Roederer, Ruinart (the longest established Champagne house founded in 1729), Veuve Clicquot (founded 1772), Krug (founded 1843), Taittinger (founded 1734) and Mumm (founded 1827). Reims is also famous for the Cathedral of Reims, the site of coronation for French kings. On the foodie side, look for Maison Fossier, an all pink shop famous for the pink “Biscuits Rosés de Reims”.

Bernard Brémont: Grande Montagne Reims

Champagne Brémont is a Récoltant Manipulant which means that their Champagne is made entirely on their property from harvesting through pressing, vinification and marketing. Bernard and Michèle Brémont created their farm Champagne Bernard Brémont in 1965. They have 12 hectares of Pinot Noir and 3 hectares of Chardonnay 98% which is in Ambonnay and 2% in Bouzy, both of which are 100% Grand Crus. The vines are an average age of 30, and are planted in clay limestone soil. They make Brut Grand Cru, Blanc de Noir, Rosé, Cuvée Prestige and a Coteaux Champenois. Son Thibault and daughter Anne have now taken over the reins continuing in the same path as their parents.

The Bernard Brémont Brut Grand Cru NV is a medium bodied white Champagne made from a blend of 80% Pinot Noir and 20% Chardonnay with a dosage of 7-8 g/l. According to IWC, we should expect “Intensely spicy nose displays bright citrus, pear and mineral scents……..Clean, finely etched lemon, orchard fruit and peppery spice flavors” on the palate.

Bernard Brémont Brut Grand Cru Millésimé “Ambonnay” 2011 is a medium bodied white made from a blend of 55% Pinot Noir and 45% Chardonnay. It shows aromas of fresh stone fruits with citrus notes, stone fruits and biscuit on the palate. The finish should have a citrus and mineral character. The Millésimé is always made from an exceptional year, selected from the harvest among their parcels best exposed.

L. Aubry Fils: Montagne de Reims

Aubry Fils is a 30 acre primarily premier cru estate in the village of Jouy-lès-Reims. Pierre and Philippe Aubry are twin brothers with a legacy dating back to 1790 and currently produce just 10,000 cases a year. The Aubry brothers have plantings of 30% Pinot Noir, 40% Pinot Meunier and 30% Chardonnay, but they are known for their exciting and distinctive wines made from a blend that includes indigenous grapes seldom seen in use today: Arbanne, Petit Meslier and Fromenteau. They prefer low yields, use only “Coeur de cuvée” in their vintage wines and typically keep the dosage low. Le Nombre d’Or is a blend of all seven Champenois grapes and the Le Nombre D’Or Sablé Blanc des Blancs is made from all of the white grapes.

Champagne Aubry Brut Premier Cru NV is a white blend of 55% Pinot Meunier, 25% Chardonnay, 20% Pinot Noir and 5% of Arbanne, Petit Meslier and Fromenteau. Half of it is made from reserve wine more than half of which came from a solera going back to 1998. We should expect lemon citrus flavors with notes of flowers, mint, crushed rocks. Robert Parker rated it at 92 points.

Coteaux Champenois is Champagne’s appellation for still wine, both white and red. The red is usually best. Reds are made in one of two styles. One is the classic style with thin and in-substantial wines except for the top estates that make elegant mineral-driven wines capable of aging for decades. Paul Bara and Pierre Paillard make excellent Bouzy Rouge wines. Georges Laval’s Cumières Rouge is another one to look for. The second style is more Burgundian making powerful concentrated red wines. Benoit Lahaye’s Bouzy Rouge comes highly recommended by Peter Liem.

Côte des Blancs

“The hillside of whites” produces mostly Chardonnay grapes (82%) on about 14,000 acres of chalky soils that produce higher acidic wines in an elegant racy style. Chardonnay adds floral notes and possibly minerality, also crispness and lightness with a well-rounded fullness that lasts right down to the finish. Vineyards are mostly east facing. Cȏtes des Blancs runs south from Épernay and has several famous Grand Cru villages: Avize, Chouilly, Cramant, Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, Oger and Oiry. Krug’s famous Mesnil-sur-Oger comes from here which Total Wine indicated a 97 point bottle of the 2000 vintage sold for a mere $1,799. Oger has now been merged into the new commune of Blancs-Coteaux.

Épernay is the smaller unofficial capital of Champagne and is located in the southern part of the region. Here you will find Perrier-Jouët, Pol Roger, De Venoge, Mercier and Moët & Chandon (founded in 1743) just to drop a few big names!

Champagne Doyard: Cȏte des Blancs can trace their family history of viticulture way back to 1677. Today Charles Doyard is a grower producer building on what his father Yannick established since 1979. That includes biodynamic viticulture, preservation of old vines and a judicious use of oak barrels. Doyard has 10 hectares in Vertus, Oger, Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, Avize, Cramant and Aÿ. They are so quality-conscious that they sell off 50% or more of their harvest each year keeping only the grapes that pass their rigorous standards of quality. Doyard intervenes as little as possible throughout the winemaking process and says “you cannot improve upon what nature gives you”. Doyard also bottles his wines at between 4 ½ to 5 atmospheres of pressure instead of the usual 6 and uses 19-21 grams of sugar for the liqueur de tirage rather than the standard 24. He prefers that the bubbles are harmonious and integrated instead of attacking you on the palate. Champagne used to be bottled at lower pressure and he wants to recreate that. Doyard makes seven different Champagnes, the most unusual being La Libertine, a doux Champagne with a light effervescence and elevated sweetness similar to the wines of the eighteenth century. Clos de l’Abbaye is made from a vineyard just behind the estate that was planted in 1956, farmed biodynamically and plowed entirely by horse. It will be bottled as a vintage dated wine each year.

Blanc de Blancs

Doyard “Cuvée Vendémiaire” NV Brut Premier Cru Blanc de Blancs (disgorged 2018) is a 100% Chardonnay white Champagne. It’s a blend of Vertus, Le Mesnil-sur-Oger, Oger, Avize and Cramant; 40% vinified in oak barrel, 20% malolactic fermentation, blend of 50% from three vintages and 50% reserve wines and 5 grams dosage. It was aged on the lees for 4 years. Robert Parker gave it 94 points, 91 points from Wine & Spirits and 90 points from Wine Spectator. We can expect intensely citrus colored, very mineral, layered flavors of honeycrisp apple, glazed apricot, candied ginger, lemon curd and a clean spiced finish.

de Venoge: Cȏtes des Blancs

Henri-Marc de Venoge set up a business in 1825, named it de Venoge Champagne in 1837 and sold his first 6000 bottles in March 1838. Shortly after he sold to clients in Brussels, Mannheim, several other German cities, London, and Copenhagen. Venoge was the first to illustrate his labels, a completely new concept in Champagne. Until then labels just showed the name of the producer and vintage. He designed an oval label with two painted bottles and the de Venoge name. Son Joseph launched the brand internationally and it was soon being sold in New York, New Orleans, Philadelphia and even Calcutta. The first special cuvées became brands in their own right: Cordon Bleu, Vin des Princes. By 1898 de Venoge was selling over 1 million bottles out of the Champagne regions entire 30 million. Today de Venoge is part of Lanson-BCC, the second largest group in Champagne after Moët Hennessy selling approximately 1,700,000 bottles annually. Their chateau is in Epernay and features a deluxe suite for rent, bar and wine shop. There are three cuvees: The “Cordon Bleu” offers Brut, Brut Rosé and Extra Brut all aged a minimum of 3 years. The “Princes of Wines” is a scale up with Blanc de Blancs, Blanc de Noirs, Extra Brut and Rosé all aged 4 years. Last but not at all least is the “Louis XV” with Brut and Rosé vintages (currently 2006 with a 93 pt rating/ no information available for the 2008) made only from grand crus and very best vintages. The de Venoge style is characterized by vinosity with freshness. They use only the first pressing (cuvée), age the wines for at least 3 years and use a low dosage of about 7 g/l. Each cuvée is quite individual expressing its terroir and grape variety.

de Venoge Cordon Bleu Brut Demi-Sec is a blend of 50% Pinot Noir, 35% Pinot Meunier and 25% Chardonnay, the same blend as the Cordon Bleu Blanc de Blanc. It was aged for 4 years and has a dosage of 40 g/l. They add 45 grams (about 3.75 Tbs) of cane sugar which enables the wine to meet the sweetness of a dessert without upsetting the balance of aromas. When left to age, it acquires delicious notes of acacia honey and makes an excellent dessert wine.

Vallée de la Marne

“Valley of the Marne River” has 81 villages and grows mostly Pinot Meunier (72%), the grape that has a fruity unctuous flavor. It is almost 22,000 acres in size primarily west of Épernay towards Paris along the Marne River which flows east to west and is known for river wines with ample body and broad generous flavor. There is one Grand Cru vineyard here, Aÿ, which is right outside Épernay.

You can find these famous houses in the Vallée de la Marne: Bollinger, Billecart-Salmon, Deutz, Gosset, Laurent-Perrier, Nicolas Feuillatte and Duval-Leroy.

Bollinger: Grand Vallée

The house of Bollinger was founded in 1829 by the son of a noble family who inherited an estate in Aÿ. One of his partners was Joseph Bollinger whose family members continue to run Bollinger, one of the most prominent producers in Aÿ as well as one of the most renowned in all of Champagne. They have 174 hectares planted with 85% Grand Cru and Premier Cru vines in seven main vineyards growing Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier. Bollinger is one of the few Champagne Houses to produce most of their own grapes to make their base blends. 60% of the vineyards produce Pinot Noir. They also have two plots, the Clos Saint-Jacques and Chaudes Terres, which have the unusual distinction of never having phylloxerra. The vines there have never been grafted and are cared for in every way possible to preserve their heritage. The exclusive Blanc de Noir Vieilles Vignes Françaises is produced from them. Grande Année and R.D. are some of the region’s most famous prestige cuvées. It’s most famous Aÿ vineyard is the 10 acre Cȏte aux Enfants which produces the Pinot Noir that is blended into the superb La Grande Année Rosé. A small amount of the Pinot Noir is bottled separately as a still red Coteaux Champenois wine called La Cȏte aux Enfants.

The Bollingers age their non-vintage wines three years and vintage wines five to eight years. The Grand Année and R.D. Champagnes are riddled by hand. No machines for these precious bubbles!

Bollinger is also unique for its reserve wine library of more than 750,000 magnums of grand cru and premier cru wines bottled with cork under light pressure and aged for five to fifteen years. These wines are used in the Special Cuvées.

Lily Bollinger managed the business until 1971 and was well-publicized in the region. Here is a noteworthy quote about Champagne supposedly attributed to Lily which I think is a great philosophy:

‘I drink it when I’m happy and when I’m sad. Sometimes I drink it when I’m alone. When I have company I consider it obligatory. I trifle with it if I’m not hungry and drink it when I am. Otherwise, I never touch it—unless I’m thirsty.”

A great marketing ploy for “Bolly” as it is affectionately known in England, was strategically displaying Bollinger Champagne in the James Bond film series. Mr. Bond ordered a bottle at his hotel, drank it at the top of the Eiffel Tower, sent it off in a gift basket, drank it after release from prison, asked for it in a casino, and had a bottle of it in his car. We hope he actually got to drink it!

Bollinger La Grande Année Rosé 2007 is a blend of 72% Pinot Noir and 28% Chardonnay from 14 crus: mainly Ay and Verzenay for the Pinot Noir; Cramant and Oger for Chardonnay – 92% Grand crus and 8% Premier. 6% red comes from the famous red wine of Cȏte aux Enfants. The 2007 has a low dosage of 7 g/l and was cellar aged for more than twice the required time. Expect a delicate coral tint with aromas of redcurrant, dried fig, mint, blond tobacco and dried flowers followed by delicate flavors on the palate of plum, kirsch, freshly cut grass and a lasting chalky finish. Wine Spectator rated it 94 points.

Gosset: Vallée de la Marne

The house of Gosset can trace its roots back to 1584 when it first produced still wine in Aÿ, making it the oldest wine house in Champagne. Back in those days, French kings preferred the wines of Aÿ and Beaune. Both made wine from Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. But in the 18th century, the wines of Ay got bubbly! Gosset cuvées of today are still presented in the antique flask identical to the one used since the 18th century. They source their grapes almost entirely from premier and grand cru vineyards in the Vallée de la Marne. Gosset makes a non-malolactic style champagne (thus preserving the malic acid in the grapes) which has become fairly unique in this region since the 1960s. To Gosset, it is not about the acidity but more about the style of their wine. Their motto is “the wine comes first, the bubbles come later”. Gosset prefers to utilize all that the grapes and terroir have to offer. They also use extended lees aging: four to five years for non-vintage, up to seven for vintage champagnes and 10 years for Celebris cuvées before release. Gosset’s style for powerful and full-bodied Champagne has changed little over the centuries. They make a range of eight different Champagne’s from Excellence Brut to Celebris Vintage Extra Brut.

Odilon deVarine, the Gosset chef de cave, continues with the philosophy

“At Gosset we first create a wine. The bubbles make it sublime”.

Gosset Grande Réserve Brut is a blend of 45% Chardonnay, 45% Pinot Noir and 10% Pinot Meunier from 3 different vintages with a 9 g/l dosage that has been cellared for up to 4 years. The grapes come from the vineyards of Ay, Bouzy, Ambonnay, Le Mesnil-sur-Oger and Villers-Marmery. The result is a bright and golden color in the glass; ripe red blackcurrants, wheat, dried fruits and gingerbread on the nose; and mineral notes with ripe and dried fruit on the palate. Rated 92 points by WE, WS and W & S.

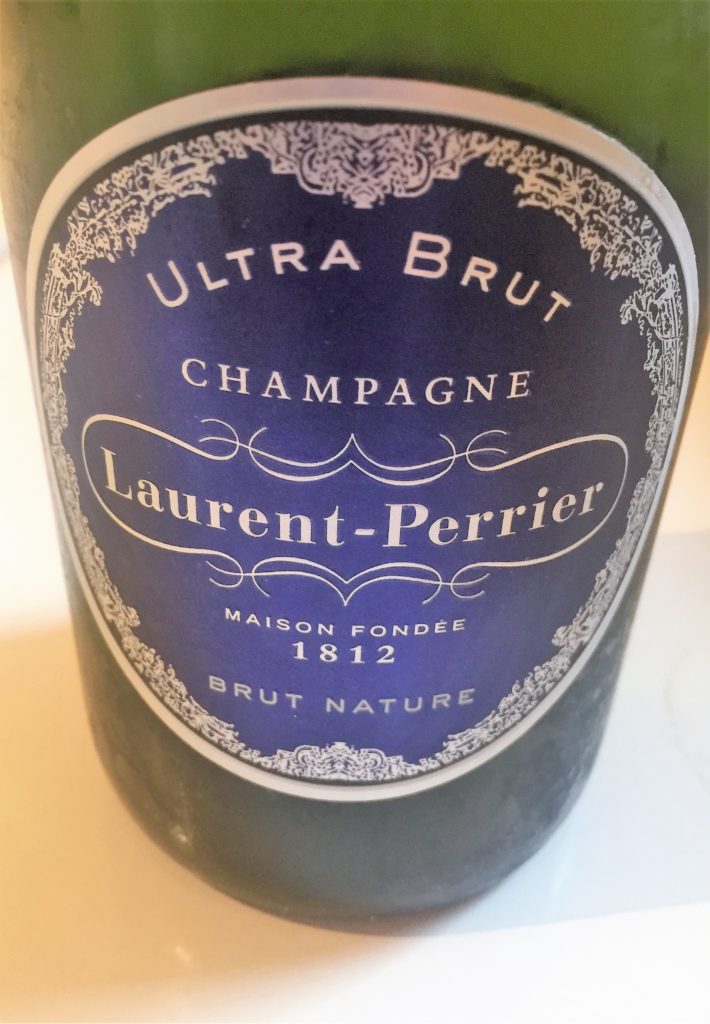

Laurent-Perrier: Montagne de Reims, Vallée de la Marne and Cȏte des Blancs

The Champagne House of Laurent-Perrier was founded by Alphonse Pierlot in 1812 in Tours-sur-Marne and eventually came to be owned by the cellar master, Eugene Laurent, and his wife, Mathilde Perrier. Eugene bought vines in the very best terroirs of Bouzy, Tours-sur-Marne and Ambonnay; dug out 800 meters of cellars and set up a tasting laboratory – a good foundation for the business. They were located in the Montagne de Reims, the Vallée de la Marne and the Cȏte des Blancs and also part of the 17 villages in the prestigious Grand Cru area. Unfortunately the company had an up and down history through various family members and World Wars until purchased by the de Nonancourt family in 1939. In 1949 Bernard de Nonancourt became the owner of the company bringing it to the level of one of the largest family-owned Champagne houses. Bernard created the signature Laurent-Perrier fresh, light and elegant style that is now exported to more than 160 countries worldwide and has made Laurent-Perrier the number 5 best-selling Champagne in the world, according to data collected by the Drinks Business in 2015. The de Nonancourt family still retains majority ownership of Laurent-Perrier.

In 1889 Laurent-Perrier started selling its zero dosage sugar-free Grand Vin sans Sucre which was ahead of its time and especially preferred by their British clientele. This wine stayed on the menu of the Jules Verne restaurant at the Eiffel Tower until 1913. The Ultra Brut Laurent-Perrier was launched in 1981 as successor to the original Grand Vin sans Sucre. They also make La Cuvée, Brut Millésimé, Grand Siècle, Cuvée Rosé, Alexandra Rosé and Harmony. Prices range approximately from $40 – $200.

The brand now controls four primary champagne brands ranging from mid-high to high to very high. The Laurent-Perrier Group (Laurent-Perrier SA) now includes the world famous house of Salon, De Castellane and Delamotte.

Salon is the most unique – it only produces one wine! It is exclusively from the village of Le Mesnil-sur-Oger and even then, only in the best vintages. Eugène-Aimé Salon began making it for his private use about 1905 and first offered it for sale in 1921. Eventually the Laurent-Perrier Group bought it along with Delamotte, which is right next door in Le Mesnil. Now the two houses share an office and facilities but not cellars. According to wine-searcher.com, the average price for a bottle of Salon Cuvee ‘S’ Le Mesnil Blanc de Blancs is $582 with an aggregated critic score of 95/100. Wine.com is offering the 2007 on sale for $580 (was $675) or if you are feeling really rich, order the 1.5 liter magnum in a gift box for $1330. It’s rated at 99 points and is 100% Chardonnay from a 2.5 acre vineyard owned by Salon plus 22.5 other acres of vineyards in the village of Le Mesnil in the Cȏte des Blancs. They only make 4 or 5 vintages in a decade. According to their website, 2007 was the last vintage released and 2008 is “currently maturing in Salon’s cellar”. The 2008, the 42nd vintage, is expected to be released in 2019 and will only be available in magnum format. Start saving your pennies!

Delamotte has been a part of Champagne since 1760. They are located right next door to the famous house of Salon. In fact at one time the owners of these two Champagne houses were married to each other. They currently make three different whites plus a rosé. A bottle of Delamotte Brut NV is rated in the low 90s and can be found for $50 – $60 with Rosé in the high $80s.

The Champagne House of de Castellane in Épernay was founded in 1895 and is now owned by the Laurent-Perrier Group. They produce both vintage and non-vintage cuvée as well as a Blanc de Blanc Chardonnay priced more in the $20-$30 range.

Laurent-Perrier Brut Nature Ultra Brut NV is a white blend of 55% Chardonnay and 45% Pinot Noir from 15 crus or villages with an average rating of 97%. As they say on the spec sheet, “it appears without make-up, in its natural form”. There is Zero dosage which requires extra care in making the wine. It is aged for at least 4 years. We should expect a very pale and crystal-bright color; citrus, white fruit and flowers like honeysuckle on the nose; a long but delicate taste of floral, fruit and mineral notes completed by a long finish with a clean palate. Wine Enthusiast rated it 93 points.

Cȏte des Sézanne

……….is just south of the Cȏte des Blancs and has mostly Chardonnay grapes planted east-facing in soils of both chalk and marl. There are 12 villages with 3665 acres of vineyard planted in 77% Chardonnay, 18% Pinot Noir and 5% Pinot Meunier grapes. Vinegrowing was virtually wiped out here by phylloxerra as most other regions, but it took years before anyone replanted. Today most of the grapes are used in négociant or cooperative blends. This region produces more aromatic wines with less acidity than Cȏte des Blanc. There aren’t a lot of growers making wine right now, but we are likely to see more activity here soon. Consider visiting Champagne Yveline Prat, Breton-Fils, Daniel Colin and Domaine Collet-Champagne.

Cȏte des Bar

The Aube, aka Cȏte des Bar with 63 villages, has mainly Pinot Noir grapes (86%) growing in marl soils that produce aromatic wine with less acidity. Wines of this region also have that body and strength from the Pinot Noir grapes. This is a lesser known region of 20,000 acres, but some wine writers have proclaimed it as “the hipster Brooklyn of the Champagne region”. If you want to break away from your norm, give the Aube a try. It is located over an hour southwest of the heart of Champagne and centered around the medieval city of Troyes, which was once considered the provincial capital of Champagne. Back in 1911, the big houses of Marne wanted to exclude the Aube from the legal limits of Champagne calling it “second-class Champagne”, but in 1927 the Aube was once again considered a full part of the region.

Sadly there are no grand or premier cru vineyards here. Since this was primarily a region of farmers, the majority of the region’s wineries are considered grower-producers who now bottle and sell their own Champagne instead of selling their grapes to the big houses. These grower-producers tend to focus more on individuality with single-variety, single-vintage and single-vineyard Champagnes being quite common. Styles differ markedly from producer to producer and vintage to vintage. Some producers to try are Cédric Bouchard, Marie-Courtin, Jacques Lassaigne, Fleury and Vouette et Sorbée.

Marie-Courtin: Cȏte de Bars

Dominique Moreau started making Champagne on a single 6 acre estate in Polisot in 2006. Her grandmother, Marie Courtin, worked on the land here during the First World War. Almost all of it is Pinot Noir and the estate has been ecocertified since 2009 and certified organic in 2010. Moreau makes only about 1000 cases of Champagnes, and they showcase their intense mineral expression. Her vineyards are close to Chablis and there is quite a bit of clay with limestone and marl, just like Burgundy. Her wines are excellent examples of single-variety, single-vintage, single-vineyard Champagnes with intense brininess and minerality. “Résonance” is named for “the balancing energies of earth and sky”, sees no wood and is a non-dosage wine giving some people reason to claim the wine is too austere while others find it to be very accessible, pure, fruity and fresh Champagne. “Efflorescence” refers to “something that evolves in perpetuity” and is also non-dosage. Dominique recommends that we serve her wines in traditional white wine glasses in order to enjoy the increased aeration.

Domaine Marie-Courtin “Résonance” Extra Brut NV is a white Champagne made from Pinot Noir grapes. It’s a wonderful example of a “grower producer, single vineyard, single vintage, single varietal and zero dosage” Champagne. Antonio Galloni tells us to expect hints of smoke, slate, dried pears and red stone fruits in a creamy expressive well balanced Champagne. He rated it at 94 points!

Roses de Jeanne, Cédric Bouchard: Cȏte de Bars

Bouchard makes single-variety, single-vintage, single-vineyard Champagnes that are completely unlike any others in the Cȏte de Bars. They are all harvested at very low yields, then fermented in stainless steel and bottled at 4.5 atmospheres of pressure instead of the usual 6. He currently makes 7 Champagnes, 4 of them Blanc de Noirs, each from its own usually tiny parcel of vineyard. His greatest wine is Le Creux d’Enfer, which is a rosé made from 3 rows of Pinot Noir, crushed by foot and macerated on its skins. It’s a perfect example of Bouchard’s natural viticulture and minimalist winemaking. Do not miss tasting Champagne from this internationally prominent tiny estate in Cȏte de Bars!

Roses de Jeanne Cédric Bouchard Val Vilaine Vineyard Blanc de Noirs 2016 is made from 100% Pinot Noir in a 1.5 hectare vineyard. Cȏte de Val Vilaine is a Pinot Noir vineyard in the village of Polisy. It was farmed organically, hand harvested and crushed by foot, fermented using indigenous yeast, then bottled unfined and unfiltered. It was aged on the less in stainless steel tanks for 16 months and bottled with zero dosage. Only 300-500 cases are produced annually. We are expecting to taste red fruit and richness on the palate similar to a red Burgundy, followed by floral and herbal notes of chamomile, white tea and chrysanthemums. Bouchard recommends enjoying the first glass with its fine creamy mousse, then decanting it and serving in large Burgundy stems at 55 degrees! CellarTracker users rate it at 92 points.

Val Vilaine Vineyard Champagne

How it’s made in Champagne

The process of making Champagne sparkling wine is known as méthode champenoise. If made the same way but anywhere else, it must be called méthode traditionelle. While there are other methods to make sparkling wine, this is the only legal method for making “Champagne” Champagne. We will talk a bit later about other sparkling wines and how they are made. This is very basic information on the making of our beloved bottle of Champagne. Entire books have been written about the process.

Méthode champenoise is basically a 9 step process. Grapes are picked gently by hand at harvest and then (1) pressed often right in the vineyard. Next up is the (2) first fermentation. In most cases the juice is fermented in stainless steel vats. After fermenting, most houses will put the wine through malolactic fermentation to soften the impression of the acidity. A typical house will have several hundred base wines while Moët & Chandon, the largest house, has 800 base wines available each year. Each producer also has a stock of base wines held in reserve every year, usually the past three years. Step (3) Blending starts in the spring after harvest until they arrive at their acceptable blended base which is call the assemblage. Next the still base wine is bottled and capped with a small amount of liqueur de tirage, which is a mixture of wine, sugar and yeast. This causes a (4) second fermentation in the bottle. The carbon dioxide produced by the yeasts converting sugar to alcohol is trapped inside the bottle. As yeasts die, they form sediment called lees inside the bottle. Champagnes are (5) lees aged in the bottle for years. During this time, a crown cap (like a beer cap) is used on the bottle. To remove the yeasts and make a clear Champagne, the riddler goes to work on the (6) Rémuage – turning the bottles upside down and slightly rotated about 25 times. Traditionally the riddling was down by hand by a réemueur. Large machines do this now especially for Non- Vintage wines. Yeast cells collect in the neck of the wine bottles but can easily be removed in a process called (7) dégorgement . The lees are removed from the bottle, and a small amount of (8) dosage, a liquid mixture of cane or beet sugar and wine, is often added. Most Champagnes contain about 8-12 grams/liter. This results in balance and sweetness. After adding the dosage, the bottles are (9) recorked – the final cork is inserted and a protective wire cage called a muselet is placed on the bottle. The final product is now ready for the market.

The cork – how do they get it in that bottle?

Simple!! It is made from three sections put together in a mushroom shape called an “agglomerated cork”. It actually starts out as a cylinder and is compressed. The bottom section that touches the Champagne is pure cork; the top two are a mixture of ground cork and glue. Over time in the bottle, it compresses into that distinctive mushroom shape. The longer in the bottle, the less it could ever return to the original cylinder shape.

Sweetness

The final level of sweetness, or Brut, is determined by the dosage. Most styles are “brut” or dry in style. All Champagne is classified according to the amount of the dosage. These are the ranges from driest to sweetest:

- Brut Nature/Brut Zero (0-3 g/l RS) – Absolutely bone dry with no added dosage or no more than 3 grams.

- Extra Brut (0-6 g/l RS) – Nearly bone dry with little to no dosage; these wines are rare; less than .6% residual sugar.

- Brut ( 0 – 12 gm/l RS) – The driest and the most popular; ranges from bone dry to little residual sugar depending on the house style; less than 1.5% residual sugar.

- Extra Sec or Extra Dry (12-17 g/l RS) – One more step drier; off-dry; 1.2 – 2 %.

- Sec/Dry (17-32 g/l RS) – Just a bit drier than demi-sec; actually off-dry to semi-sweet; 1.7-3.5%.

- Demi-sec (32-50 g/l RS) – Half-dry; medium sweet, not as sweet as doux dessert wine, but suitable for many desserts. Demi-sec means “half sweet”; 3.3-5%.

- Doux (50+ g/l RS) – A rarely produced dessert- sweet Champagne style; minimum of 5%.

Styles of Champagne

There are a number of styles of Champagne, but they are almost all blends. The Champagne maker may make hundreds of still wines to use as bases in the final blend (called the assemblage), but they are all made using one of Champagne’s three grapes. Blending is considered the most critical skill a winemaker can possess. Champagne houses build their reputation on the style of their blend of their non-vintage wines, so it has to be consistent. Champagne is also aged on the yeasts, and the legal length of time for aging varies depending on the style.

Brut is the most common and most popular style of Champagne. It refers to the driest of bubbles and can contain anywhere between 0 – 12 grams per liter of dosage, or final level of sweetness as previously described. There are different levels of Brut – Brut Nature/Ultra Brut with 0 – 3 grams or Extra Brut at 0 – 6 grams. Note that Extra Dry and Dry are actually not as dry as Brut. If you are looking for a bubbly to serve with dessert, try the Demi-Sec or rarely produced Doux. They can have from 32-50 grams dosage.

Non-Vintage NV is the most traditional of the Champagne styles. Multiple varieties and vintages of wine are blended together in hopes of producing a consistent wine every year. Grapes come from good vineyards but not Premier or Grand Cru although some Premier Cru may be blended in. Some houses prefer to use Pinot Meunier grapes only in Non-Vintage because they do not age as well as Chardonnay or Pinot Noir; therefore you will almost always find Pinot Meunier in Non-Vintage wines. Non-Vintage must age on the yeasts (sur lie) for a minimum of 15 months – 1.5 years.

Vintage or Millésimé is a traditional Champagne made only in certain years. There have been 46 years denoted as Vintage in the last 60 years. Eighty percent of the grapes used in a Vintage wine must come from the declared year. These grapes come from good to great vineyards: many are ranked Premier or Grand Cru. Pinot Meunier is sometimes included in a Vintage wine. Vintage must age sur lie a minimum of three years prior to release.

Prestige Cuvée is also a traditional Champagne and is the very best wine a Champagne house produces. It is the tȇte de cuvée of “Grand Cuvée”. These grapes come from the greatest vineyards, historically ranked Grand Cru. Pinot Meunier is rarely included in a Prestige Cuvée by most houses. There is no legal requirement for aging sur lie, but common practice is four to ten years. Some famous examples of Prestige Cuvées are: Louis Roederer Cristal, Laurent-Perrier Grand Siècle, Moët & Chandon Dom Perignon, Pol Roger Sir Winston Churchill, Veuve Clicquot La Grande Dame and Perrier-Jouëts Belle Epoque.

Blanc de Blancs “white from whites”is non-traditional and made entirely of white grapes like Chardonnay. It generally goes well with lighter foods, such as seafood and vegetables, is also good as a pre-dinner aperitif. They may be Non-Vintage or Vintage and are generally expensive. One of the most expensive there is was created in 1921 by the founder of the Champagne house Salon. Blanc de Blancs are treasured for their lightness and generally come from the Cȏtes des Blanc. Two of the most extraordinary Blanc de Blancs in the world are Krug’s Clos du Mesnil and Salon’s Le Mesnil.

Blanc de Noirs “white from reds”, also non-traditional, is made completely of red grapes such as Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier. It has a slightly pink tinge and deeper golden color than the Blanc de Blancs and makes a great pairing with full-flavored foods, i.e meat and cheese. These Champagnes tend to be rare and expensive.

Rosé is traditional and typically a blend of white and red wine to create a rosé or pink wine prior to secondary fermentation. Thank goodness the “Pink Champagne” of the 50s and 60s is no longer made! The color comes from the addition of Pinot Noir wine at the second fermentation, the point at which still wine becomes Champagne. This type is one of the best to have with dinner, according to Ed McCarthy, author of Champagne for Dummies. These are richer and fuller-bodied and are considered the cream of the crop. They are usually more expensive than golden Champagnes because they are more difficult to produce and they are rarer. They are made from one of two methods: (1) The Saignée Method, which is the most historical, involves letting some of the base wine sit in contact with Pinot Noir skins until the wine color is tinted pink or (2) A small amount of still Pinot Noir wine is added into each Champagne bottle before the second fermentation. Champagne is the only wine region in Europe where it is allowed to make rosé by blending white and red wine, rosé d’assemblage.

Single vineyard Champagne is made entirely from a single plot of vines instead of blending from many different plots. It can be Non-vintage or Vintage. One of the most famous is Krug’s Clos du Mesnil, first vinified in 1979 and released in 1986.Marie-Courtin and Cédric Bouchard are both grower producers currently making single vineyard Champagnes in Cȏte des Bars. Cédric Bouchard makes exclusively single vineyard, single vintage Champagnes at his Roses de Jeanne estate.

Did you know they also make a still pink rosé wine in Champagne? Rosé des Riceys is made in Les Riceys, the southernmost village of Champagne. Les Riceys is the largest wine growing village in Champagne at 2140 acres. Only 865 of those are approved for rosé.

The Grande Marques and Maisons de Champagne

The Champagne Houses battled since the middle of the 19th century to protect the name of “Champagne” from being used by producers outside their region. This was before the days of appellations and legal protection. They joined forces with the Champagne Growers and drafted rules governing Champagne production, starting with demarcation of the area itself. The Champagne region was mapped out in 1927 by the Institut National des Appellations d’Origine Contrȏlé (INAO). This began the concept of the AOC. Champagne is just one AOC unlike Burgundy with over 100 and Bordeaux with more than 50. In 1936 the region of Champagne was successfully decreed the Champagne AOC. This decree also ratified all of the other laws and decrees of 1919, 1927 and 1935. The name Champagne is protected even from use by other regions in France.

In 1941 the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne (CIVC) was formed for the purpose of protecting Champagne’s name, reputation and monitoring regulations for vineyard production and vinification. The CIVC has established the classification system by grading the land based on suitability for growing white or red grapes. The 17 Grand Cru villages are graded at 100%; Premier Cru from 90-99%. The rest range from 80- 89%. The producers set the price of their raw materials used upon the percentage rating of their grapes. The price a grower gets for his grapes is also determined by this system.

The rules regarding the labeling of a sparkling outside of Champagne, France are strictly enforced by French national laws, European Union regulations, and international trade agreements and treaties. When the laws are broken, lawsuits are quickly filed.

What about California, you may ask? Korbel, a California winery, actually labels their sparkling as “California Champagne”. Their website says they use méthode champenoise to make it. It is definitely not made in Champagne, France. It seems that the United States had a grandfather clause written into those agreements which said that “wineries who were operating and producing sparkling wine before the agreement was signed in 2005 are legally (according to US law) able to use the term “Champagne” on their label”. But most don’t. Korbel does but has been the subject of much controversy.

There are nearly 350 Champagne Houses. Most of the major houses are members of the Union de Maison de Champagne (UMC) and are sometimes referred to as Grandes Marques. The Champagne Houses themselves have additional specific criteria that must be met to meet the AOC regulations. Three are general criteria and seven are specific to each Marque.

General criteria basically refer to production, marketing, communication and research. Specifics refer to their production contracts, quality control procedures, reserve stock, base wine selection and blending, aging procedures, disgorgement and procedures for foil wrapping and release.

Most Champagne Houses are known for their brand promise with an unchanging taste profile. Each Cellar Master is responsible year after year for that taste in the bottle – quite a responsibility!

Négociants, Co-ops and Grower Champagnes

Historically the business model for Champagne has been that “growers” provide the grapes and Champagne houses or Maisons, also known as négociants, buy the grapes from the growers, produce the Champagne, and send it off to market. However this model has changed some since as early as the late nineteenth century.

The type of producer marketing the Champagne can be identified by a two letter abbreviation followed by the producer’s official identification number on each and every bottle. These codes have nothing to do with its quality.

- NM Négociant manipulant: These companies, including most large brands, buy grapes from growers and make the wine. A Négociant can also own wine, too.

- CM Coopérative de manipulation: These are co-ops that make and sell wine from growers who are members.

- RC Récoltant coopérateur: A co-op member sells grapes to a cooperative and then receives Champagne produced by the co-op to sell under the members own name and label.

- ND Négociant distributeur: A wine merchant that buys finished bottles of Champagne and then sells under his own label and/or name (Kermit Lynch?)

- RM Récoltant manipulant: A producer that makes Champagne exclusively from their own vineyard. Their Champagne is usually referred to as “ Grower Champagne”

Grower Champagnes are made by small growers who usually make artisanal style Champagnes. They don’t buy the grapes as the large Champagne houses do – they grow their own and produce their own. This “farmer fizz” as some wine writers call it, is their wine from start to finish. The base blend is usually much simpler since they probably are not growing that many different grapes. The resulting Champagne really reflects the terroir of the place where it was made. According to Karen MacNeil in the Wine Bible, some grower-producers to know are: Pierre Peters, René Geoffroy, Pierre Gimonnet, Gatinois, Doyard, Michel Loriot, Jean Milan, Varnier-Fanniere, Chartogne-Taillet and Jean Lallement.

- SR Société de récoltants: A group of growers, usually family members, who make Champagne from their own vineyards.

- MA Marque auxiliaire: A buyer’s own brand; for example, a supermarket that buys the Champagne and then sells it under their own label.

Organic and biodynamics

Attitudes of the Champagne producers have been shifting remarkably during the past two decades. They are now making an effort to improve their farming methods and have discovered the results may make better wine. The Comité Champagne has put region-wide initiatives in place to educate the growers about sustainability. For example: reducing the use of pesticides across the appellation by 50%, avoiding insecticides, creating recycling systems for the use of water in winery operations, initiating recycling programs for materials such as crown caps, and developing a lighter Champagne bottle which reduces carbon emissions.

There are a few organic producers but not many due to the wet climate of the appellation. It is cool and damp and mildew is a constant threat. Even fewer growers are certified biodynamic although many may use some of the methods and preparations. Marie-Courtin in the Cotes de Bars is both organic and biodynamic. Fleury was first to become certified biodynamic and Louis Roederer is the largest biodynamic vineyard holder.

The hot topic among vintners for the next decade is the use of the metal copper. Copper sulphate is used by organic wine producers in lieu of pesticides to control mildew infection in the vines because copper is allowed as an agricultural practice while synthetic chemicals are not. European law has recently decreased the amount of copper that farmers can use because it degrades very slowly once washed off the vines and enough of it can lead to lifeless soils. It has been reported that one in five organic wine producers currently use more than the new copper limit. This leaves both the organic and biodynamic vintner with a major problem – what to use to control mildew? The biodynamic approach is to promote soil life and vineyard health. They will also have to find a satisfactory biodynamic alternative, and you could possibly see fewer organic farmers in the future.

Here’s the dirt………or all about the terroir

First of all, “terroir” is about so much more than just dirt. It is climate (coastal or continental), precipitation, heat (moderate, tropical, arctic), sun exposure, altitude, slope, how vineyard rows are oriented, vegetation, wind, humidity (we really hate mildew), fog, severe weather (hail, frost, drought, floods and wildfires are great threats!). And of course it is “soil” – the composition, the color on the surface, stones on the surface, drainage, and microbial beings like yeasts and bacteria. All of these are elements of the “terroir” and when the terroir gods all align, the grape grower is off to a wonderful start. It is up to him/her to take it from there!

Champagne’s climate is predominantly “maritime” like most of France. It’s influenced by the Atlantic Ocean on the west. The annual temperature ranges about 50 F. Summers are usually warm, winters usually cold and rain is steady throughout the year. Sometimes unfortunately the weather is also “continental” – there can be frosts, heat waves and hail. We have already talked about how weather affected the harvest for 2018.

Now there is just one element missing – the white soil of Champagne is more than 75% limestone and in many places chalk. It is those famous chalky soils that make Champagne so special! Chalk is a specific type of porous limestone. But how did it get there? The region lies in the Paris Basin, which is a massive bowl-shaped formation of many layers of sedimentary rock that cover most of northern France. More than 72 million years ago in the Cretaceous period, this area was covered by a large sea. The sediment of tiny fossils and calcareous algae formed the chalk in a thick layer, up to 1000 feet deep in some places. The chalk is responsible for the brisk saline character of the wines and also helps to regulate the supply of water to the vines. Those tiny fossils exist in two principle biozones – ancient squid with a beak made of calcite are found in the belemnite or upper portion, and tiny fossilized sea urchins make up the micraster or lower portion. Not all types of limestone are good for grape growing, but lucky for Champagne – they got the chalk!

Comité Champagne

Each village has a slightly different soil makeup which gives the resulting wines a slightly different flavor profile famous for that particular historic terroir. Parts of the Champagne region don’t even have any chalk. For example the Cȏte des Bar is in the southeast, accounts for almost one-quarter of Champagne’s vineyards, and is made up of the same type of soil as Chablis – Kimmeridgian limestone and marl (calcareous clay). The new generation of winegrowers in the Cote des Bar are becoming famous for their single vineyard single variety philosophy which especially showcases the terroir. The majority of vineyards in Montagne de Reims, Grand Vallée and Cȏtes des Blancs all sit on chalk. The chalky soil in the Cȏtes des Blancs is exceptionally white, pure, covered with minimal topsoil and is perfect for Chardonnay. This is why some of the very best Blanc de Blancs in the world come from this sub-region.

The grape growers and wine makers have been making incredible Champagne in this region for many years working with the terroir that they are given. Most of their work was in the cellar blending the wine. Hopefully the famous Champagne Houses will be making champagne in the styles they have become known for many years to come. But the new generation has brought along with it technology and process improvement to allow making the very best use of the terroir. Now there is increased attention paid to both the cellar and the vines. That can only have a good outcome for consumers and serious winelovers like us!

Crayeres – the famous ready-made wine cellars

Have you visited the wine cellars of Ruinart in the city of Reims? If so you have probably experienced some of the 250 or so “crayeres” in existence. These are deep chalk pits originally dug about 2000 years ago to quarry chalk for building material and other purposes. They are pyramidal in shape, typically with a narrow opening that widens out as you go deeper, and they can be 100 feet deep. It turns out that these pits make the perfect place to store wine due to their humidity and temperature. Ruinart was the first to use them for this purpose and today has cellars extending for 5 miles underground. In the 1860s other Champagne houses began to use them, too. Taittinger, Charles Heidsieck, Henriot and Veuve Clicquot all have lovely crayeres, but Pommery takes first place! Madame Pommery acquired 120 crayeres in the 1870s covering more than 11 miles of rooms and tunnels. Then she hired an artist, Gustave Navlet, to carve huge designs into the walls taking over 3 years to complete. The crayeres are strictly Champenois and exist only on the southeastern side of Reims.

Photo by Michel Guillard; courtesy of Comite Champagne

The rules of “Champagne etiquette”

- Serve chilled but not too cold – no colder than 6 C (42 F) and preferably around 12 C. (53F) if rosé, vintage and older wine. Don’t over chill. Too cold is almost worse than too warm! The ideal serving temperature is between 42 -48 F. Fill the ice bucket to within an inch of the top with half ice and half water; make sure the entire bottle is submerged. Assuming room temperature of 68 F, allow 40 minutes to chill a Champagne cellared at 52F but at least two hours for Champagne at room temperature, possibly longer. The ice bucket brings the temperature down gradually then keeps it there. It should stay at proper temperature for about as long as it takes ice to melt.

Don’t have an ice bucket? Allow 2 ½ – 3 hours in the refrigerator with the bottle laying on its side. Then drink fast! That Champagne will warm up quickly without ice!

- Don’t hide the label when serving by wrapping the bottle in a towel. That is considered a social faux pas. Always make sure guests can see the name of the producer while you are pouring. Wipe the bottle when you take it out of the ice bucket to avoid dripping all over your guests. If you MUST use a napkin, tuck it under the bottle leaving the label fully exposed.

- The right glass is essential. Whether you are using a flute, white wine or tulip glass, crystal glasses are the best. Tulip glasses are now considered the gold standard. More about the glass selection later in this article.

- The proper way to open a Champagne bottle is as quietly and unobtrusively as possible. Popping the cork is actually considered bad manners not to mention dangerous. The bottle pressure can launch a cork at a speed of 13 meters/second which is slightly faster than the time it takes to “blink an eye”. Each bottle is under 6 atmospheres of pressure which is about the same as a truck tire. Here is how to do it:

- Take bottle out of ice and wipe dry with a napkin.

- Carefully turn bottle upside-down once or twice without shaking to ensure proper temperature throughout.

- Present the bottle to your guests – please show them the label!

- Hold the bottle in one hand at 30-45 degree angle pointing bottle away from everyone.

- Break and remove the foil, but not the wire cage from around the cork.

- Place your thumb firmly on top of the cork to keep it from flying.

- With your other hand, carefully unscrew the wire about 6 turns and loosen the cage.

- Holding the cork firmly, twist in one direction until the cork quietly eases out making that small sigh of escaping gas meaning it is released. Be sure to turn the bottle, not the cork.

- Wipe the bottleneck keeping bottle at an angle and give it a slight twist.

- Fill the glass only one-third full by holding the bottle directly above the glass to encourage bubbles but prevent excessive foaming. Avoid filling more than half or two-thirds full to allow for bubbles dancing in the glass.

- The sommelier or host/hostess will expect you to nose and taste the Champagne before nodding your approval. Don’t swirl!

- Never never place an empty bottle upside down in the ice bucket. That shows complete disregard for your Champagne!

- Savor it with short sips but if required to gulp it all down, the French call this sabler le Champagne.

- If it is between meals, Champagne tastes best with some plain savory dry “biscuits” and even better with some nuts, green olives or Gruyere if its Brut and sweet biscuits with Sec or Demi-sec. Here is where some Fossier Rose de Reims mini-biscuits would be perfect!

How BIG is that bottle?

Here are the sizes of bottles currently approved for sale within the European Union:

- Quarter: 20 cl (or 18.7 cl on board ships)

- Half bottle: 37.5 cl (12.7 ounces)

- Standard bottle: 75 cl (25.4 ounces)

- Magnum: 1.5 litres/2 bottles (50.8 ounces)

- Jeroboam: 3 litres/4 bottles (101.6 ounces) (1); the first king of Israel (930-910 BC)

- Rehoboam: 4.5 litres/6 bottles (147 ounces) (2); son of Solomon and king of Judah (930 – 915 BC)

- Methuselah: 6 litres/8 bottles (196 ounces) (3); lived for 720 or 969 years depending on source

- Salmanasar: 9 litres/12 bottles (304.8 ounces)(4); the name given to five Assyrian kings.

Very large sizes made only to order (5)

- Balthasar: 12 litres/16 bottles (406.4 ounces)

- Nebuchadnezzar: 15 litres/20 bottles (508 ounces)

- Solomon: 18 litres/24 bottles

- Melchizedec: 30 litres/40 bottles

Solving the mystery of food pairings

Nothing quite equals Champagne as a single wine to serve throughout a meal. It is also a wine for all seasons and all events. It’s great in the summer no matter whether dining indoors or al fresco. It’s great in freezing winter weather of the North or the balmy winter weather of Florida. And it should never be saved just for celebrations or major events. It’s perfect as a toast, an aperitif, or served throughout an entire meal. But it still deserves some thought and consideration for choosing the perfect Champagne. The right one also pairs with your dessert course or just drink it by itself for dessert.

If serving Champagne with a full-course meal, serve the various styles in order of intensity: light before strong, young before old and dry before sweet. Just remember to go from lighter to heavier flavors. The main elements to consider are flavor intensity and structure together with the texture. If opting for a single Champagne throughout the meal, go with the heavier weight, more intense flavors of a vintage and/or prestige cuvée. This is a good rule of thumb to follow for serving through the courses: Brut NV for beginnings; Vintage and Prestige for the main course, and Demi-Sec for dessert. Here are some more in-depth pairings:

Appetizers: This is a great time to serve Non-vintage Brut or Blanc de Blancs. A fairly young crisp tasting Blanc de Blancs will go perfectly with cheese tartlets, mini-toasts topped with smoked salmon or foie gras, and nuts, especially almonds. No sweet appetizers or pizzas please. Caviar also goes with youngish Blanc de Blancs. If you haven’t tried potato chips or popcorn for finger food snacks or appetizer, you may be amazed at how well it pairs. Champagne pairs well with salty foods particularly dry styles like Brut Natures.

Seafood: A non-vintage Blanc de Blancs is best. Pacific oysters go best with young Champagne while Maine Belon oysters are a treat with a mature Vintage Champagne. Oysters Rockefeller, langoustine, scallops and lobster require older drier Vintage Champagne. Escargot with a Blanc de Blanc works well as do caramelized scallops with an older vintage. Try some grilled salmon with rosé.

Fish: Serve a Blanc de Blancs with a freshwater fish like trout in a creamy buttery sauce. Saltwater fish like sea bass and sole call for a Non-Vintage Brut Blanc de Noirs. The lighter the sauce, the lighter the Champagne. Making Bouillabaisse? Pair it with a good Rosé.

Charcuterie: A Pinot Noir driven Vintage Champagne is a good choice for hot foie gras.

Poultry: Vintage or Non-Vintage Pinot Noir driven Champagnes are good matches for chicken and capon. Any poultry involving mushrooms calls for an older Brut or a Rosé. Only an old really mature Champagne can match up to truffles.

Meat: Brut Vintage is delicious with veal, braised ham or pork (especially tenderloin). Red meat – especially less fatty cuts of beef and lamb served rare – must have a good full-bodied rosé as do beef stew and osso bucco. Chinese and Thai food need a Demi-Sec.

Cheese: Coulommiers cheese with a Brut Non-Vintage is a pairing made in heaven! Camembert, Reblochon, Comté and Brie are also good choices, but never pair with Blue cheese. Fresh young goat cheese works wells with a Blanc de Blancs or light Non-Vintage Brut.

Looking for cheese from Champagne? Langres AOP cheese is a soft creamy slightly crumbly washed rind cow’s milk cheese from the Langres plateau in the French region of Champagne-Ardenne. It has had its own AOP since 1991. Langres is famous for its cylindrical shape with a 5-mm deep well on the top called the “fontaine”. The rind has a natural orange color. Wine and cheese aficionados fill the well with Champagne and eat the cheese after champagne has bubbled out from the top “volcano-like”.

Chaource AOP cheese is another cow’s milk cheese from the Champagne region, specifically the village of Chaource, where it has been made since the Middle Ages. It is 50% fat, creamy, crumbly and spreadable with a taste something like a Brie. It goes really well with a Rosé Champagne. Chaource has been AOP accepted since 1977.

The “pudding”/dessert: If you must, try a Blanc de Blancs with a chilled peach soup or a Rosé with a strawberry tart. If you are serving anything sweeter, particularly involving chocolate, you should switch to a relatively sweet Champagne. Bittersweet dark chocolate can also pair with an extra dry or dry style. Fresh berries are nice with Rosé. For a simple sweet finish fill glass bowls with fresh cherries, raspberries and blueberries, which bring out the Champagne’s hidden fruit flavors, especially with a Rosé.

To end the evening: Here is where you pull out the rare and extravagant Prestige Cuvée to sip at leisure in comfort ………maybe with a fine cigar?

Breakfast, brunch and supper: Non-Vintage Brut should do fine for the entire meal. If the occasion is more special, you may want to switch from Brut to Demi-Sec for dessert.

Between meals and anytime: A basic Brut Non-Vintage is all you need to bring people together.

The glass is the thing!

2016 may well have marked the death of the Champagne flute. Many sommeliers and wine experts have given up their flutes for glasses that better showcase their bubbly beverages. Flutes may well signify that the event is a celebration, but according to Axelle Araud, a wine expert at Dom Perignon, a white wine or burgundy glass not only “keeps the aroma in the glass, but gives the Champagne more room to express what it has to say”. Classic flutes are permissible for non-vintage Champagne as they “preserve the effervescence” but to pay homage to those vintages and most special cuvées of the Champagne producer, use the white wine glass.

Maximilian Riedel, CEO of Riedel Crystal, told Decanter.com that “his goal was to make Champagne flutes obsolete”. Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, cellarmaster at Champagne Louis Roederer said: “we often use white wine glasses” to aerate their Champagne. Hugh Davies, CEO and winemaker at Schramsberg Vineyards said that a classic narrow flute can inhibit the depth of aroma and flavor in the wine.

Where do the bubbles come from? Professor Gerard Liger-Belair is a chemical physicist at the University of Reims and an expert of sparkling wine bubbles. The Professor says 1) there are 10 million carbon dioxide bubbles naturally present in a bottle, 2) the size of bubbles can vary from between .4 mm and 4 mm, 3) it is not true that the smaller the bubbles, the better the champagne and 4) 1.7 mm across seems to be the magic size for a bubble. When the bottle is opened, those 50 million or so tiny bubbles inside are set free! Shall we count and measure? Scientifically they explode as they reach the surface of the wine making a tiny crater. The crater then closes up and ejects a thread of liquid which break up into droplets that can fly up to 10 centimeters. Tiny strings of bubbles come from certain points in the glass. Microscopic fibers left by a kitchen towel or just airborne particles stick to the side of the glass allowing the molecules of dissolved carbon dioxide to form bubbles. So it’s possible if you drink your Champagne from a glass that has been so ultra-cleaned and dried that there is nowhere for the bubbles to form. That is not a problem when I wash wine glasses!

So why do we have flutes? They showcase those tiny bubbles that look so beautiful rising to the top of your glass. They actually have a small scratch at the base that whips the wine into a tiny tornado and encourages it to stay bubbly as you drink. It also makes it easy to measure your pours. Flutes are also harder to spill than the coupe and saucer glass popular 50 years ago. And they look so fun and festive signifying “it’s party time”! Sorry but it has been scientifically proven that a coupe loses CO2 at least one-third faster than a flute.

The coupe design was supposedly modeled on Marie Antoinette’s left breast! But it actually came about before her time. It was designed to allow the drinker to dip cake into its shallow bowl – after all, let them eat cake! It came back into vogue a few years ago especially for serving our trendy cocktails. My Florida 57 cocktail at Point 57 Restaurant in Cape Coral would not have been nearly as exciting to me if served in a different type of glass!

Some head sommeliers such as Philippe Jamesse, head sommelier at Les Crayères in Reims so detested the use of a flute that he took his idea to a local glass manufacturer Lehmann and they created what they consider the perfect glass – an elongated, rounded in the middle and tapering towards the top measuring 72 – 88mm at the widest point – depending upon how much money you want to spend! Some of the great Champagne houses like Ruinart, Piper-Hiedsieck, Moët & Chandon and Krug have all collaborated with Riedel to create glasses tailored to specific wines. Some of them even believe that each vintage requires a specific glass to best showcase their wine.

Riedel’s family has been making high-end glassware since 1756, so they obviously know a few things about making the “perfect” glass. Their newest Fatto A Mano champagne glass is shaped like a white wine glass with the scratch point set in the center of the bottom of the glass, and it costs a whopping big $100 a glass! A little too much for my Champagne taste on my Prosecco budget. According to some taste testers using the Fatto A Mano glass the champagne smelled far more appealing due to the wider mouth, the bubbles lasted longer and the taste stayed fresher. The essence of flowers or fruit come forward instead of the yeasty mushroomy smell from a flute. Riedel also says the best substitute for such a champagne glass is a Pinot Noir glass because there are so many Pinot Noir grapes used to make champagne.

Riedel is still happy to sell flute glasses, but their recommendation for sparkling service would always be the wine glass shape, so if you order a sparkling wine, especially a vintage Champagne, don’t be shocked if your restaurant sommelier and staff presents it to you in a white wine or tulip style glass. Or ask for service in a white wine glass (or a red wine glass if their glassware is small). They and you will be ahead of the curve!

Try a glassware testing at your next Champagne event

The Champagne:

Do two separate taste tests – one a Non-Vintage Champagne and the other a Vintage

The Glassware:

- Pour Champagne in several types of glasses: flute, white wine or tulip, coupe and maybe even a Pinot Noir Burgundy glass if you are feeling really adventurous.

- Consider how it changes in each one:

Is it more aromatic or less?